It is well known that the human being has always wanted to approach the stars. Whether he has tried with wings (like Icarus) or by building higher and higher, it is also obvious, but it is clear that if by building one goes lower, it was still safer. Suddenly, the first projects of towers go back very far in the time, but the techniques of construction not being developed, these projects often remained in the state of project. Again, let's not talk about the Tower of Babel, probably one of the first failed projects ...

More seriously in the late nineteenth century the tallest buildings were just 150m high, the fault of materials used until then, stone and masonry, which could not withstand too much pressure, so at too great a height. (see the Reasons for the choice of iron for more explanation on this subject)

At that time the tallest buildings in the world were limited, most of them were great achievements, masterpieces recognized by all and each nation drawn a legitimate pride. We had, for example:

- The spire of the Invalides dome, in Paris (105m)

- St Paul church, London (110m)

- St Peter's Cathedral, Rome (132m)

- The pyramide de Khéops, Cairo (142m)

- The Cathedral in Cologne (156m)

- The Washington Obelisk (169m)

- The Mile Antonelliana Tower in Turin (170m)

But to climb even more, and much more than one could conceive at the beginning of the industrial era, it was necessary to use another material, metal, and more particularly cast iron and iron. Before the Eiffel Tower stood in Paris, showing the technological prowess achievable by the French, other projects were born, but none have actually been made. The very first was the reform tower, but it was far too far ahead of its time, and unfortunately imagined by a utopian rather than an entrepreneur.

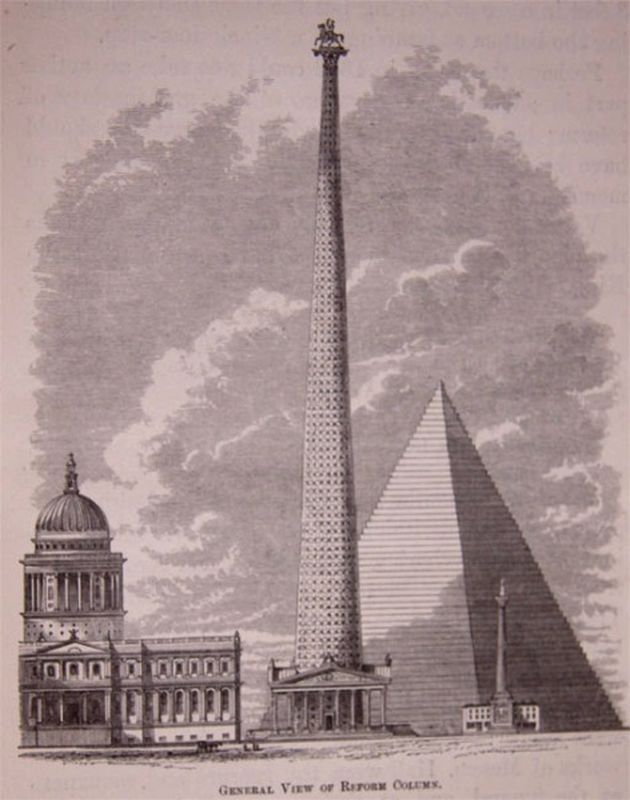

1804: The Reform Tower

Thanks to the appearance of metal as construction material it was possible to build higher, much higher. This gave the architects ideas as well as engineers, with the ambition to achieve this 300m high tower. The first to embark on the adventure was Richard Trevithick, an English inventor (1771-1833).

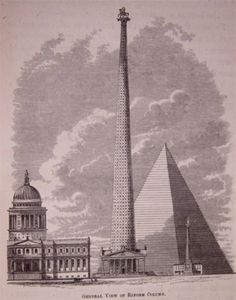

The Reformation Tower

It is said that his tower was supposed to be covered with gold, but one can imagine that it was only a view of his mind and not a future reality. On the other hand this project was quite serious and a priori roughly calculated. This tower would have been called the reform tower, in reference to the 1831 reform that took place in England. In the representation opposite it is put in relation with the cathedral Saint-Paul and the Great Pyramid of Giza. This huge open-cast iron column 1,000 feet high (which is exactly 304m and 80cm) should have 30 meters in diameter at the base and leave in the shape of truncated cone until 3m60 at the top. A somewhat unlikely elevator system was planned: An observation platform inside the column had to be propelled to the top by a steam-powered air cushion system. But this project has never really been studied, let alone realized. Richard Trevithick died poor and forgotten of his contemporaries as much as today, but it was he who was at the origin of the mechanical steam systems that provoked the industrial era. It is only his lack of courage that has prevented him from succeeding in actually building his machines instead of remaining as projects.

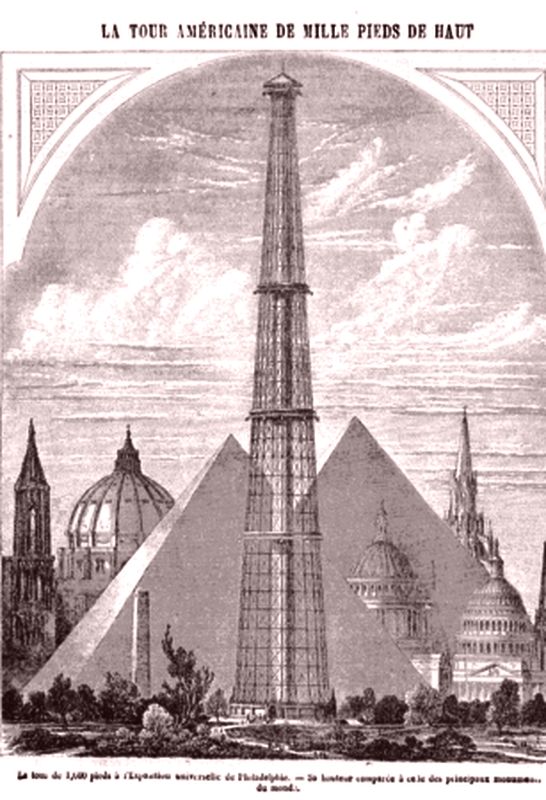

1874: The Tower of Clarke and Reeves

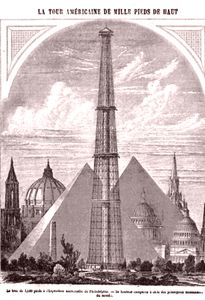

The tower Clarke-Reeves

It was not until 20 years before we spoke of this famous tower of 1000 feet. It took place on the occasion of the Exposition of Philadelphia, in 1876. It is during this exhibition that Auguste Bartholdi introduced the first pieces of the Statue of liberty, in the making. It was during the preparation of this exhibition that a serious 300m metal lathe project was conceived. It has also been described in the scientific journal "Nature" by two distinguished American engineers, MM. Clarke and Reeves. (No. 42, March 21, 1874) It was a 9-meter-diameter tower-cylinder, held by metal stays arranged all around and attached to a base 45 meters in diameter. This project, as interesting as it was, has never been realized, either because of lack of resources, lack of time, or even lack of will. But the most important thing was that the project was realistic and achievable at an acceptable cost.

Note that this tower was actually designed on plan two years before the exhibition, in 1874.

To be as exhaustive as possible here is the text of the magazine Nature, that of March 21, 1874 in which the description of the tower has been translated. The original text appeared in the journal Scientific American!.

The plans are from Messrs. Clarke, Reeves and Company, engineers and owners of the Phoenixville Bridge. The materials consist of American wrought iron, in the form of Phoenixville columns. They are joined by diagonal tie bars, and supported by horizontal supports. The section is circular; it is 150 feet in diameter at the base, and rises diminishing up to 30 feet in diameter at the summit. A central tube, 30 feet in diameter, occupies the center of the tower. An elevator will be able to climb to the top in three minutes and go down to five 500 people per hour. Around the central tube there will be spiral stairs.

With the construction system used, the tower will be as rigid as if it were made of stone, while presenting a very small surface to the wind. The proportions are such that the maximum of pressure resulting from the weight of the building, loaded with people, and by a lateral pressure of a strong wind will not exert on the lowest row of the column a tension too considerable. The estimate of the price of the work gives a figure of one million dollars and the time required for the construction, according to the plans, will not exceed a year. The location has not been definitively determined yet, but probably it will be Fairmont Park in Philadelphia, not far from the centuries-old exhibition buildings. The tower and its surroundings will be lit at night by an electric light and the view of the surrounding country will be incomparable.

It is needless to add that the character of the project is related to the purpose of its erection. The hundredth anniversary of our national existence was not to pass without a permanent memory, which an exhibition of a few months can not provide. It is evident that in the space of two years no monument of such imposing appearance, of such an original conception, could be constructed with other materials than iron; from all points of view we could not choose a more national construction. We will celebrate the day of our birth with the most gigantic iron construction that man ever conceived.

The Scientific American! review concludes by saying, with national pride, that it is good to point out that the plan of the 1000-foot tower was designed by American engineers, that the work will be directed by American mechanics, and that all materials will be exclusively borrowed from American soil. Is there not in this subject something bold, grandiose, truly worthy of our admiration.

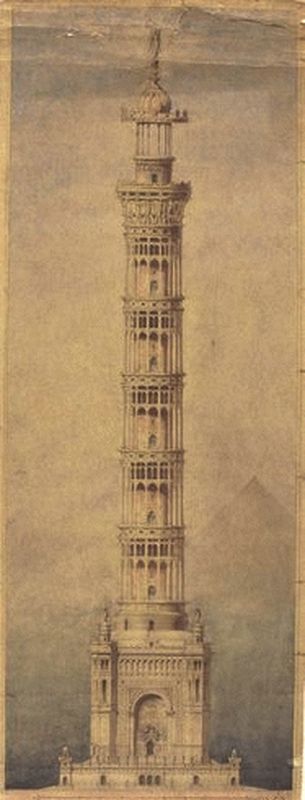

1881: The Sébillot Tower

The sun tower Sébillot

In 1881, another project appeared through Mr. Amédée Sébillot, electrical engineer, who was returning from America with the drawing of a 300-meter iron tower surmounted by an electric fireplace for the lighting of Paris. But if the tower itself was interesting, its purpose was rather crazy and the project was not completed. The project was in the form of a "Sun Tower", ie an immense tower topped by a gigantic electric lighthouse that would have illuminated all Paris, from Levallois to Vincennes, the Bois de Boulogne, etc. . The tower itself would have been in granite surrounded by cast iron columns forming superimposed galleries, the total diameter being 18m. The tower would have been mounted on a triangular base whose height would have exceeded, alone, the towers of Notre-Dame (the project provides a 66m high base). It would have contained a museum dedicated to electricity. Above the somital lighthouse was the laying of a winged statue of the genius of Science, as well as an observation platform that could have held 1000 people.

This tower was designed by engineer Sébillot. As he wanted to be realistic, he associated himself with the engineer Jules Bourdais who had a good reputation, it was he who had built the Trocadero Palace in 1878. However the architect did not really foresee the weight of his work and, as explained in the introduction, this fantastic mass of masonry would have required gigantic foundations totally unrealizable, with the greatest chances that the monument collapses under its own weight. He never had the slightest chance of really getting out of the ground, but the project did exist concretely.

Enlighten Paris from a huge tower, idiocy?

Can we really imagine lighting up Paris from the top of an immense tower? If this question seems crazy nowadays it was not the case at the end of the 19th century. Amédée Sébillot was an electrical engineer, he went to the United States to perfect his knowledge and discovered on the spot real applications of arc lamps that have the characteristics of producing a bright light. On the basis of this principle of illuminating towers, some cities in the United States had tried public lighting and force experiments and noted that such a system had not only been realized, but was effective, but for a small neighborhood only. And it had the disadvantage of leaving large areas of shadows, all the more important as the top of the tower was low. But among the pilot cities at this San Jose project in Texas, there was a metal structure some 50 meters high along which many arc lamps had been placed, and it worked quite well.

Thus the project of lighting Paris was not so crazy that that, at the end of the XIXe century. It was enough for the tower to be tall enough, and the lamps mighty enough to reproduce a system similar to that of San Jose. The lighting designed by Amédée Sébillot was based on a set of 100 arc lamps of 20,000 carcasses distributed in a crown of 12 meters in diameter and 36 meters in circumference. Above the lamps, an immense reflector towards which the beams are directed redistributes the light towards the city and "to the interior of buildings and houses". Above the reflector, a crown of "real projectors with parallel beams", imagined by the engineer, made up for any deficiencies in the general fireplace and brought additional light where it was needed.

1889: Meanwhile, a French entrepreneur was working ...

Still, during this time the young Gustave Eiffel was trained on the techniques of construction in cast iron, then in iron, and had a great experience in building railway bridges. When he also designed his 1000-foot tower, he first presented it to the curators of the Barcelona World's Fair in 1887, but they did not follow through on this project, considering it too expensive. It was therefore to the commissioners of Paris that he addressed himself, and those who gave the green light for this project.

Once completed, this famous 1000-foot tower, later called "Eiffel Tower", was imitated. Nowadays there are a lot of copies around the world. But at the end of the construction some originals wanted, more or less seriously, to make even bigger towers in different cities. The best known is undoubtedly the Watkin's tower, the only tower designed to compete with Paris having been really but partially realized.

1891: The Watkin's tower

The Watkin's tower is a tower that was originally supposed to be taller than the Eiffel tower, it was to be 350m high. Coming out of an international competition with some particularly crazy proposals, it was Watkin's project that stood out. It must have been an octagonal tower but at the time of construction the calculations were redone for a square-based tower, like the Eiffel Tower. Construction began in 1891 but it stopped as the first floor was built, for some reason. In 1907 this structure was demolished, marking an end to this project.

The Judson Project

An engineer from the United States, Mr. W.-L. Judson, proposed a Tower of 490 meters. It seems designed to show that greatness does not exclude ugliness. If it is destined to make the glory of America, it will certainly not be in architectural things. It is true that its author claims not to have stopped at these details of aesthetics. By fixing this elevation, he wanted, not only to give it a rock solid, but above all to make it a gigantic advertisement for a kind of pneumatic traction tramway of his invention. Now, to give this tramway a role in his monument, he employs it to mount the travelers to the summit by an inclined road, spiraling around the building. This colossal spiral involved a form of candle, which is far from the best in terms of the use of materials used, and Mr Eiffel will not be jealous.

A company is offering to build Mr Judson's Tower, for the modest sum of 12,500,000 francs which, it is thought, would soon be covered by the price of ascents, fixed at one dollar (6 francs from the time). The new Tower would have, indeed, a capacity of transport whose elevators of the Eiffel Tower can not give an idea.

Two helicoidal, independent and superimposed roads would rise from the base to the summit with a width varying from 22 meters at the base to 15 meters at the summit. Each would make seventeen complete circuits, and would have a developed length of 6 kilometers, with an average slope of 8 per cent. One of the tracks would be delivered to vehicles of all kinds, and one could reach the end in his own car; the other would be reserved for a double tram line of the Judson system, each carrying sixty passengers and departing every half-minute. The Tower would be 128 meters in diameter at the base, its central core, cylindrical, would be 84 and would be divided in its height by ten circular floors, whose use is not yet indicated. It is proposed to establish huge popular hotels there.

Money does not have the same value in America as in France; life is very expensive, but the wages are very high, and the working class people never hesitate to spend a few dollars for a pleasure, for a new sensation. We can therefore admit the accuracy of the forecasts of the promoters of this company. They would make a good deal and Mr Judson would have his claim. As for aesthetics, business people are very concerned about it. Moreover, this Tower would not be more ugly than most factory chimneys.

It goes without saying that this tower never saw the light of day.

The Grai Hinsdale Project

An American counterproposal, emanating from Mr. Grai Hinsdale, emerges the idea, original if not very practical, to group all the buildings of a future world exhibition in a symmetrical way around a huge metal pylon, connected to the ground by arches, four in number. The first would affect the octagonal shape and measure, from the base to the upper dome, a height of about 400 meters; the outer arcatures would be welded at 330 meters above the ground, and would still be connected by others, at 150 meters, the latter having to carry a huge floor similar to that of the first floor of the Eiffel Tower, and intended for the same purposes, concerts, restaurants, exhibitions of all kinds, etc. This floor would be large enough to receive and circulate all visitors of the same day, or 300,000.

The feet of the main arcatures would be on a circumference of 760 meters in diameter, and it is between their fallout that the buildings of the exhibition would be established. Elevators, four in arcature, two for the ascent and two for the descent, would lead the visitors from the ground to the upper platform: the traction would take place by a funicular system, with cars suspended from rollers on a upper track. From the platform, sixteen other lifts would take the audience to the dome. It would also be accessible by six elevators starting from the floor 150 meters above the right of each of the lower arches; finally, twenty other lifts would operate in the very interior of the central pylon, from its base to its summit. The cost of establishment would be 50 million francs.

The excessive cost of this construction would probably be enough to condemn it; but to this argument is added so many others, that it is useless to insist on a project destined not to be realized, and which will never be realized.

The Kinckel project

A New York architect, Mr. Charles Kinckel, proposed to build a 500-meter elevation tower, cylindrical and non-pylonic. It would be built in the middle of a rotunda 80 meters high and would group, like the previous one, forty-eight iron buildings, in which one would install the various sections of an Exhibition.

The Horizontal Tower

Another project is still betting a horizontal tower, resting on a base on one side and, on the other, on a platform where people wishing to rise to 300 meters would enter a living room. shape of sphere bypassing an axis. Machines, using cables and pulleys, would then straighten the monument on top of which one would be thus transported as if by magic!

The Proctor Tower

The Proctor Tower project, destined for the Chicago Exposition, was a steel construction and would be 365.26m high and would be completed by a huge flagstaff. Ten elevators would take visitors to the various floors, four would serve for the first landing, 6l meters from the ground, two for the second, 122 meters, with a stop at the first, and two others would go non-stop to the third. Finally the last two lifts from the second and third floors, would rise to the dome at 365 meters above the ground. The total capacity of all these elevators will be 8,000 people per hour in one direction and 16,000 in both directions, that is to say in the ascent and descent. From the base to the summit, the Tower would be a beacon of electric light with projections of extraordinary strength at the top, which would illuminate the entire expanse of the grounds of the Exposition.

In all probability, it is the hydraulic force that would be used to operate the elevators. But the pressure pumps supplying the water to the hydraulic cylinders would still be activated by the electric motors. Messrs. Molobert and Roche, renowned architects in Chicago, and Mr. C. T. Purdy, mechanical engineer, are the initiators and would remain the directors of the construction of this Tower, which would affect the classic shape of the Eiffel Tower.

The Colombian Tower

The unitary Republic of Colombia wanted to have its project as well. The Colombian Tower was to surpass the Eiffel Tower and present new principles of architecture. The construction and operating company has a capital of 12,000,500 francs. The Tower would be built on arches placed on six foundations placed 125 meters apart and resting on a layer of blue clay at 5 or 6 meters below ground level. The Colombian tower is 385 meters high. At 66 meters there would be a floor; a second at 160 meters; a third at 300 meters; a fourth at 385 meters. Ten elevators of the Haie system would serve the travelers, eight would go to 160 meters and the other two to the summit. Fifty thousand people could circulate simultaneously in the Colombian Tower. The promoters are Compagnie G-A. Fuller, the Haie Lifts Company, and the Carnegie Smelter, Pittsbury. These are all powerful companies, but this project could not be realized.

See also: